The carbon tradeoff

This is installment one of a four-part carbon series written by AgriWebb’s Vice President of Sustainability, Nicole Buckley Biggs, PhD.

Today, I’m launching a 4-part AgriWebb series focused on carbon and grazing. My goal is to provide a broad perspective on carbon opportunities, without shying away from the pros, the cons, the challenges, the choices. So to kick-off, here’s our first topic:

Producers can EITHER sell offsets OR low-carbon beef, but not both.

Carbon offsets are getting a lot of attention as a source of income for farmers and ranchers. For some, offset payments can make a real difference in reducing financial debt and economic challenges, a reality that many grazing operations navigate daily. Some project developers even offer upfront financing to producers to help reduce the cost of fencing and water infrastructure development, including Native’s Help Build™ program working with producers in the Northern Great Plains.

That said, it’s still important to know that offsets are just one of a few ways you can improve your financial outlook as a grazing operation. Not only that, but signing an offset contract can take other options off the table – in particular, the option to sell low-carbon beef at a premium.

So why can’t you sell carbon offsets and also sell low-carbon or carbon-neutral beef? Essentially, because if you’re a landowner who has contracted to sell carbon offsets, you don’t own that carbon anymore to apply to your own livestock. In other words, grazing operations that sell offsets have sold the right to claim the carbon benefits they achieve. So you now face an important choice: sell carbon offsets or market your products as being climate friendly.

Given the public’s concerns about climate change, producers may want to prioritize producing lower-carbon beef, lamb, leather and wool over producing carbon offsets. Otherwise, the next generations may find it impossible to continue operating in an industry so heavily criticized for its climate footprint.

That may seem dramatic, but we already see public and government pressure squeezing producers in different countries. We see it with New Zealand’s new proposed methane tax on its agriculture industry starting in 2025 and the Netherlands’ shutting down agriculture in the name of climate. Similarly, in the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission is considering a proposal to require greenhouse gas emissions reporting for all publicly traded companies, which would put additional pressure on farming operations.

Beyond government regulations around climate, big climate commitments are also coming from the private sector. 83% of Fortune 500 companies have already set climate targets, and we can expect 80-90% of the beef supply chain in developed countries to be under a corporate climate commitment soon, including a 2030 target.

How do these commitments impact the carbon offset market? The leading standard that companies follow for reducing their emissions is WWF’s Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). That standard doesn’t allow carbon offsets to be used to reach climate targets. This means that grocery stores, restaurants and other companies need to show actual improvements in reducing their own emissions, with farm level data to prove it. This is part of increasing global pressure on companies to actually reduce their own GHG emissions, without which there is increasing risk of legal action for companies that depend on carbon offsetting as their climate strategy.

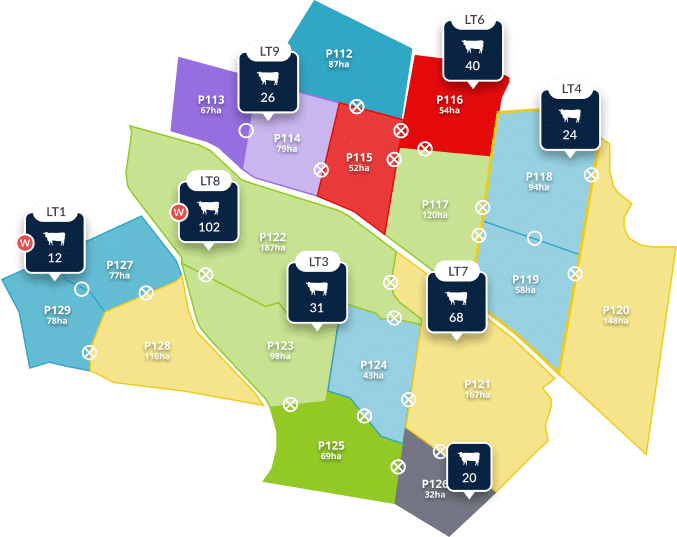

When companies make investments into their own farms to try to reduce their GHG footprint, it’s called “carbon insetting“. Carbon insetting is an alternative to companies buying offsets generated by other industries. Food and agriculture companies have been slow to launch formal insetting programs, largely because they’re treading carefully to avoid reputational issues and greenwashing critiques. But over the next year, we can expect most major companies that purchase beef (see Figure 1) to announce a carbon insetting program.

Given all this, food and agriculture corporations with climate commitments are now competing with carbon offset developers for carbon claims. In the past, climate targets were largely set by other industries outside of agriculture, and those other industries could purchase offsets from agricultural landscapes to address their own emissions. Now, with the food and agriculture industry setting its own climate commitments, emissions reductions and carbon removals on agricultural lands will be needed for the industry’s own progress reporting.

In this new climate reporting landscape, grazing operations that have carbon offset contracts in place (i.e., selling carbon to other industries) could be at a disadvantage when it comes to carbon insetting projects. That said, carbon offset developers are offering contracts today to help producers be paid for laid stewardship and reduced emissions, while most carbon insetting programs are still in the works for grazing lands.

Figure 1. Major global brands with ambitious Net Zero targets

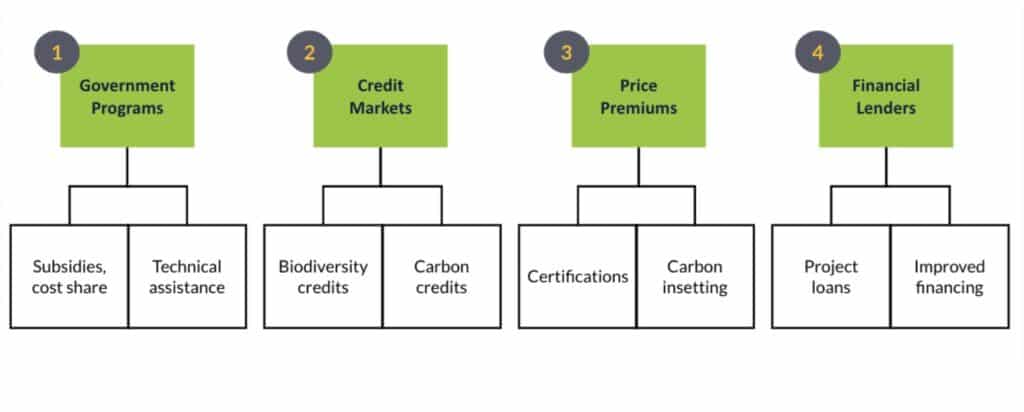

Grazers should know that carbon offsets and insets are just two ways to be compensated for an improved environmental footprint. Whether you’re working on reducing methane emissions through improved animal health and productivity, or improving carbon drawdown through pasture diversification or managed grazing, there are basically four options on the table for sustainability-based revenue.

Offsets fall within the category of ecosystem service markets, or markets created to pay landowners for storing carbon, improving biodiversity, or providing other environmental benefits. Beyond these biodiversity and carbon credit markets, producers can also be rewarded for sustainability efforts through government programs, price premiums, or financial loans (see Figure 2).

For example, US farmers can apply for Farm Bill funding through the USDA, with the help of a local extension agent or FarmRaise. These programs can help cover the cost of new fencing and water infrastructure, cover crop seeds, and other sustainability interventions. Another option is to market sustainable or low-carbon beef at a premium, whether Director-to-Consumer or through a supply chain. Or, in some cases you may qualify for a ‘green loan’ from an agriculture lender because you’re investing in sustainability, or get improved rates on your existing loans. Farmers can compare all of these different opportunities, and how they’ll impact their bottom line now and in the future, when considering what to do on carbon.

A key thing to note: some of these revenue sources are stackable. That means you can pursue multiple sources of revenue. For instance, ranchers can get funding from NRCS for water pipelines to improve grazing management, and then later also sell their beef at a premium under a sustainability certification. However, not all revenue sources are stackable and in some cases there’s a tradeoff – for instance, having to choose between selling carbon offsets or low-carbon beef.

Figure 2 Four Approaches to Sustainability Driven Profit

And that’s a wrap. Next Wednesday, I’ll dive into a related topic in Part 2: Upheaval in the carbon offset market. I’ll focus on how carbon offset markets are changing because of issues with existing methodologies, and what resources grazing operations can use to better understand their options