Biodiversity net gain explained

What is Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG)?

Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) is a concept that the government and Department for Environmental Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) aim to bring into place from November 2023. Its goal is to mitigate the negative environmental effect of development, leaving nature in a better condition than it was before. From the end of 2023, developers will have to demonstrate how they will replace the biodiversity lost as a result of their new development.

They must calculate the biodiversity of the pre-development site and improve that by at least 10%. Although local authorities can increase this by as much as 25%. This increase in biodiversity must be maintained for 30 years but can be achieved off-site. The biodiversity is calculated as units.

That’s where farmers come in. There is a potential revenue for landowners to sell biodiverse patches of land which account for the biodiversity units developers require.

At the moment, this will only be operational in England.

How do you calculate BNG?

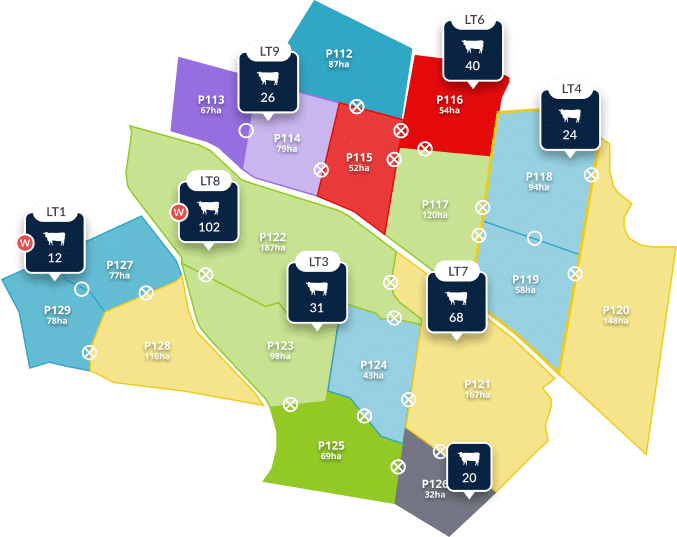

DEFRA calculates biodiversity units using a biodiversity matrix. They consider the extent of the land, as well as its quality, distinctiveness and condition.

But how big is a unit and how much money can it generate?

Typically, sites will produce 2 units per hectare. Payments per unit vary massively from £3,000 to as much as £80,000 over the course of 30 years. Using the estimated average of £20,000/unit, farmers could make £1,300 per year which would reduce to about half that after sowing, maintaining and monitoring the land.

Is this really about improving farm practices and who’s it for?

Incorporating biodiversity units onto farmland may be better for larger farms as a smaller proportion of the land will be taken out of production. However, it is possible for farmers to still work the land that is set aside for a biodiversity unit. For example, you might consider the creation of a wildflower meadow that you can mow once a year and use for hay.

By incorporating biodiversity units into working farmland, farmers don’t necessarily need to take land out of production. Growing hedgerows, digging ponds or planting trees can all be achieved alongside livestock farming. It should be part of the goal for farming in a more sustainable and environmentally friendly way.

Farmers can also stack credits from the different schemes. The same land set aside for biodiversity credits could also be eligible for the Environment Land Management Scheme. Biodiversity and carbon credits can be awarded for the same parcel of land.

Case Study: Hallam Mills, Hampshire

Hallam Mills farms along the River Avon in Hampshire. He is a dairy and arable farmer with some forestry. At first, he was put off by the long-term agreements but has decided to push ahead with a BNG audit. It has helped him to understand the environmental value of his land and changes he can make to improve its biodiversity. His poor quality marginal land was unproductive but the BNG provides him with some income during incredibly volatile times.

How can landowners get involved and what should they be aware of?

There are three ways for farmers and landowners to sell their biodiversity units.

Firstly, they can sell directly to the developer. As no one else is involved, this creates the biggest income for the landowner. But it also poses the greatest risk. The landowner would be solely responsible for the success of the biodiverse plot of land. If it fails, then it is up to the landowner to rectify the problem as they will have to answer to the local authority. They would also need to foot the costs to create the biodiversity in the first place.

Secondly, landowners can work the deal through a brokerage service. This ‘middleman’ sets up meetings and deals between the farmer and the developer but takes a cut of the profits for doing so. It is considered medium risk to the landowner.

Thirdly, Environment Banks are a less risky strategy to help manage the land. A signed Farm Business Tenancy Agreement between the landowner and the company means that the capital costs of setting up the biodiverse land is covered, and a management plan agreed. It is a long-term agreement which may span two generations adding a level of complexity, but income is secured over the time period.

Other things to consider about biodiversity net gain

The government is still deciding what level of tax relief, if any, might be applicable for BNG land. With a minimum agreement of 30 years, there could even be inheritance tax implications.

There are still questions surrounding the end of the 30-year agreements. Uncertainty remains whether the land can be placed back into production. Many believe this would be unlikely. Consider whether this would affect your future plans for the farm or any growth you may have envisioned. Equally, having a biodiverse-rich farm could fit well with other enterprises you are planning such as ecotourism or recreation.

The demand for BNG units will vary greatly between local authorities. Areas higher in development such as the southeast of England will have more demand as will areas where there might be a limit on available land.

Where is best to start?

The best advice is to start small. You don’t need to put the whole farm into the BNG scheme. Start with just a single field and see how the management works or whether it is right for you before expanding.

Talk to AgriWebb about how you can use your data to help with BNG or carbon calculators.