What’s in it for me? Livestock – arable rotation

With regenerative farming or a return to traditional farming frequently coming up in conversations, we look at how a livestock – arable rotation might benefit farms.

What does a livestock – arable rotation look like?

Over the centuries farming has become specialised within the UK. Arable farming is most common in the east, livestock farming in the west, and mixed farming as a strip running from north to south in the middle. Recently, however, these farming practices have been seen as problematic and a return to mixed farming could be the way forward.

Livestock introduced as a rotation on arable farms could produce a multitude of benefits from soil health and weed management to alternative revenue streams and lower risks. Both types of farms benefit from the arrangement and these can vary greatly. They can be as simple as exchanging straw for manure or as complex as tenancy agreements or joint business ventures. Integrated farming could also be more environmentally friendly, reducing the impact of agriculture on the environment.

There are many different reasons why a farmer may turn to livestock – arable rotations.

What are the benefits of a livestock – arable rotation?

Arable farmers

Rotating arable crops with grazing grasses or herbal leys can significantly improve soil quality. The variation in plant species and their variable root depths improve soil structure and nutrient content. Livestock grazed on the fields enhance soil nutrients through their manure. Sheep can contribute up to 35% of soil organic matter.

If legumes are also sown into the mix, then the benefits of nitrogen fixation can prove invaluable. Legumes can capture as much as 150kg/ha of nitrogen every year, much of which is left as residual in the soils for subsequent crops. This means that arable farmers won’t need to use as much fertiliser on their crops the following season, reducing costs and effects on the environment.

A cheaper weed control?

Weed control is an arable farmer’s biggest nightmare. Alopecurus myosuroides, otherwise known as blackgrass, is a herbicide-resistant weed. Its rapid reproduction and growth mean it outcompetes cultivated crops and reduces yields. Estimates suggest this drop in production costs England £0.4 billion each year. Herbal leys and livestock grazing can outcompete the weed and break its life cycle.

Fields can be used to host livestock from a neighbouring farm or to grow forage crops such as silage and maize for animal consumption. The climate and weather can make or break an arable farmer each year. Droughts and floods, which are becoming increasingly common, can devastate harvests. By diversifying into livestock farming, arable farmers have an alternative revenue stream and can spread the risk of production.

Tapping into some of the government payment schemes can be achieved through growing forage for livestock. These include ryegrass seed-set as winter food for birds, which can provide hay, silage and grazing for livestock and pays £331 / ha. Growing winter cover crops is another revenue source which can be grazed by overwintering livestock and pays £115 / ha.

Livestock farmers

Livestock farmers using arable land can reduce the cost of production. Farmers just starting out cannot always afford land to graze their livestock. Renting arable land or owning it in a joint venture can be a way forward for new farmers or those looking to expand without incurring significant costs.

Grazing livestock on fresh clean pasture will reduce the need for anthelmintics and therefore can improve the health and reduce the cost of the animals.

What are the challenges of a livestock – arable rotation system?

The biggest challenge is establishing a relationship with another farming enterprise and getting started. For arable farmers, introducing livestock can be a daunting prospect. Growing catch crops and fattening lambs or overwintering ewes on them can be a good, low-risk place to start.

The set-up costs can be off-putting for many arable farmers wishing to integrate livestock on their land. You should consider infrastructure costs and how to establish herbal leys. AHDB have created a cost calculator to help farmers work out the profit margins they can make from branching into a livestock – arable rotation. This considers everything from fencing, water troughs and ley establishment to machinery, fuel and vet bills. Take a look at the calculator here.

What sort of agreements might work?

It’s best to first ask yourself what your goals are when considering introducing a livestock – arable rotation. The answer to this may just determine what sort of system may work on your farm and what agreements to go for.

The simplest muck-for-straw deals could be a way of integrating the two farming types. The arable farmer will provide straw whilst the livestock farmer hands over organic, nutrient-rich manure in return.

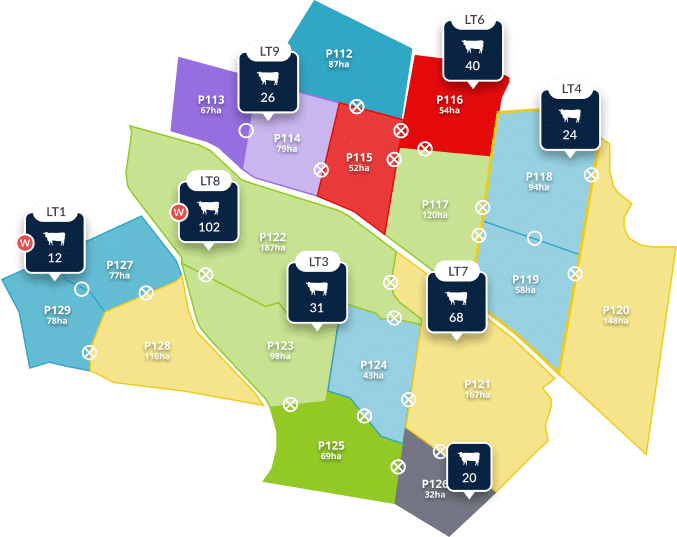

A variety of grazing agreements exist. For example, some where the landowner rents out the land and claims subsidies on it. The grazier, meanwhile, uses the land to graze livestock without income or additional rights. A more formal grazing licence can secure land for the grazier for two years or more and gives them more security in terms of land use. In either case, a livestock farmer with limited access to land, may be able to identify a system whereby stock move between one agreement and another on different land.

Tenancy agreements are used when the grazier rents land from an arable farmer. It is a more formal contract that works well with established relationships. The next step up from this are joint ventures which can include contract farming agreements. Both parties must be willing to collaborate and costs, labour and profits are split. See this useful calculator from the AHDB.

What to think about in terms of agreements

Agreements should be made in writing and the specifics of the relationship should be made clear. These should include things like who is responsible for livestock welfare, who claims subsidies, and how the workload is split.

It may not be as simple as allowing another farmer to graze livestock on your land. Animal welfare should be at the forefront with regular checks and visits by experienced personnel. Consider whether you need fencing for livestock, shelter and water provision. Of course any animal movements should be in accordance with the law.

It’s important to note that some fields may not be suitable for grazing animals. If there is a risk of run-off, then plant buffer strips or prioritise fields with good soil drainage. Some will be less susceptible to soil erosion and compaction than others.

With the right agreement, both arable and livestock farmers can benefit both in the short and long term from a mutual relationship. Furthermore, we can secure the future of sustained farming and the future of our soils through a more integrated approach to farming.

To find out more about grazing capabilities within AgriWebb, click here. If you’d like to go through an walkthrough of our grazing add on features, click here.