(Spoiler: It’s not just seaweed or rotational grazing.)

Companies like McDonalds, Walmart and JBS have made ambitious commitments to reducing the climate footprint of the beef they sell by 2030. With 2030 right around the corner—literally five calving seasons away—are these goals possible to achieve? If so, what are the paths to success?

When we talk about carbon footprints in agriculture, there are two key goals: reduce both absolute emissions and emissions intensity per unit of product. Global focus is often centered on the first: for example, through calls to reduce beef consumption. Yet given growing consumer demand for meat, companies must also figure out the latter: how to reduce the emissions associated with producing one unit of beef.

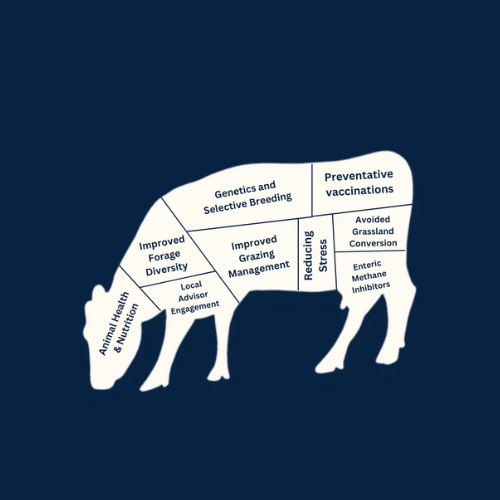

With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at three opportunities for reducing the carbon intensity of beef using strategies that are feasible to implement, backed by strong research, and best of all, can improve a producer’s bottom line:

- Animal Health and Genetics

- Feed and Nutrition

- Avoided Grassland Conversion

The first two on this list are largely focused on reducing methane emissions by improving weight gain, reducing days to slaughter, and reducing morbidity and mortality. The last one, preserving intact grasslands, falls within the “nature-based solutions” category of interventions, and is targeted at preventing soil carbon losses rather than reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Animal Health and Genetics

Improving animal health and productivity tackles the largest single source of beef emissions: methane. A recent analysis from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that improved productivity and efficiency could reduce global livestock emissions by 30%. Some example interventions in this category include preventative medicines, reducing animal stress, preventing calf losses, genetic selection, and improved grazing management.

How does improved animal management reduce methane? It comes down to developing a system that produces the same amount of beef, but more efficiently and with less loss.

For example, preventative vaccinations play a major role in herd health by combating common diseases, whether respiratory, digestive, reproductive, or otherwise. An Oxford Analytica analysis predicted that expanded use of vaccinations would improve livestock production by 35% in upper-middle income countries and by 53% at a global level. Another consideration is reducing stress, which can both diminish fertility and increase mortality. To prevent these negative outcomes, producers can adopt new practices like low stress handling techniques or providing livestock improved access to shade and water to reduce the chance of heat stress.

Improved grazing management is another critical tool for improving animal health and welfare, which among other benefits can reduce parasite loads. Parasites are a common challenge on grazing operations and have been shown to increase methane emissions in addition to reducing production efficiency. Parasite loads can be managed with medical interventions like dewormers and through rotational grazing, which disrupts the parasite’s lifecycle by removing the necessary host.

Preventing calf losses can also reduce the carbon intensity of beef. By one estimate, 4% of cows in the US do not raise calves past two weeks of age (North Dakota State University Extension benchmarking report). In Australia and Canada, studies have estimated that approximately 8% of mated females fail to deliver a calf, due to abortions, stillborns and deaths before weaning. While some causes of cattle abortion can be difficult to control, neonatal calf health can be improved through proper colostrum management, reduced stress, and vaccines.

Beyond direct health interventions, genetics and selective breeding can also make a significant impact by producing more meat per cow and reducing carbon intensity. An example is breeding for improved fertility, longevity, and growth rates. Since 1975, the US has improved productivity enough to expand overall production even with a decrease in its herd size. These gains were largely the result of increased animal weights, accomplished through selective breeding for higher growth rates and feed conversion efficiency.

Notably, the benefits of improved animal health and productivity at the grazing level are commonly passed through the supply chain as healthier, more feed-efficient cattle move to the feedyard, resulting in reduced emissions. One challenge for corporate sustainability programs is aligning incentives when interventions are implemented at the ranch level but do not provide benefit until the stocker or feedyard, and yet still support overall emissions reductions.

When looking at climate-smart practices, one should note the importance of local advisors in helping producers with these challenges. Extension service agents and veterinarians typically provide support to producers in diagnosing and addressing health issues, and are best positioned to advise on the appropriateness of specific practices. According to surveys, extension agents are also the most trusted source of information for beef cattle producers, after other producers.

Feed and Nutrition

Beyond health and genetics, grazing operations can also use nutrition and forage quality improvements to augment productivity. Example approaches include improving feed digestibility, seeding pastures with legumes, and improving the nutrition of winter feed. A variety of substances can improve digestive efficiency in cattle, whether protein feeds, oils and fats, minerals, salt, urea, or forages with high tannin content. Both lipids and essential oils have also been shown to reduce methane emissions in cattle by an estimated 10-20% in some studies.

Many producers today feed supplemental minerals to cattle to increase conception rates, improve weaning weights, and improve immunity. Trace minerals like cobalt, zinc, and phosphorus are critical to livestock growth, and when supplemented, can make up for what is lacking in the local environment.

Another approach is improving forage diversity, which enables cattle to choose the plants that optimize their nutrition, while avoiding toxicity issues that can arise when few plant species are available. Some producers plant legumes like sainfoin and alfalfa, which can be more easily fermented in the cow’s rumen and improve nutrient use by the animal. Improved productivity outcomes have been documented when cattle graze on diverse forage.

A slightly different approach is to use feeds known as enteric methane inhibitors to manipulate a cow’s rumen so that it produces less methane. The main methane inhibiting feeds used today are 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) and seaweed containing bromoform. A 2022 UK study estimated that beef GHG emissions could be reduced 22% with methane inhibitors (CIEL 2022). Methane inhibitor feeds can reduce enteric methane significantly, but can also pose their own challenges and are largely in the development stage today. Canada recently approved 3-NOP as a feed additive for reducing methane in cattle; we may soon see this option for corporate sustainability programs in other regions, including in the US as producers await FDA approval.

One challenge with feed-based solutions is that they are best suited for environments where cattle are fed more intensively, like in feedlots. Some grazing operations do provide supplemental feed, but in other cases that can be quite challenging because of difficult topography, remoteness and lack of equipment or labor.

Producer access to local advisors is again of key importance. According to the US Department of Agriculture, only 11% of US grazing operations consult an animal nutritionist, with typically only the largest operations accessing this type of support. Expanding producers’ access to technical assistance is critical for improving the adoption of these practices.

Avoided grassland conversion

Finally, there can be no sustainable beef without grazing lands. As much as we hear about the potential for rotational grazing to improve soil carbon, the larger soil carbon opportunity is in preventing grassland conversion, one of the biggest threats to grazing lands today (see here for more details on drivers of grassland conversion).

In 2021 alone, 1.6 million acres (650,000 ha) of grassland in the US and Canadian Great Plains were destroyed and plowed up, mainly for crops. Besides being a biodiversity catastrophe, this kind of land conversion drives significant soil carbon losses. In fact, in a 2012 issue paper prepared by The Climate Trust, experts concluded that up to 2M metric tonnes of CO2e could be avoided each year due to prevented grassland conversion in the US. And this is by no means a US-specific issue; research in South America has estimated that converted croplands lose seven times more carbon than managed grasslands. Maintaining intact grasslands should be a priority for companies looking at the long term sustainability of beef supply chains, and a top priority for conservation action. Longer term, actually increasing soil carbon stocks through rangeland management may offer another opportunity for reducing the carbon intensity of beef, but scientific research is still in development to accurately measure these dynamics.

And now the big question: how can McDonalds, Walmart, and JBS drive action around these solutions?

The most impactful way is to invest directly in helping producers to implement practices in these three strategic areas. In doing so, corporations help to improve livestock productivity, as well as producer livelihoods. By financially rewarding producers who improve their practices, companies enable real climate action while improving their green credentials in the public eye.

When companies have implemented sustainability initiatives without financially rewarding producers, the resulting traction with farmers is weak or even counterproductive—for example with the UK’s Red Tractor green scheme that was dropped last week following farmer pushback.

The added benefit of financial incentives to producers is they reduce land conversion by enabling recipients to see the profit associated with keeping their lands in grazing. Corporations can also invest in conservation easements, although this can be an expensive option unless done in coordination with an NGO or government agency. The exciting thing about the solutions described here is that they all offer strong co-benefits for animal welfare, producer profitability, and long-term land stewardship.

—

A final note: I mentioned at the beginning that both absolute emissions and emissions intensity matter. One concern out there is that if productivity improvements drive profits, that overall production will increase and drive up herd size, resulting in higher absolute emissions. Given this, it is critical that both metrics be tracked over time, to show that productivity gains do not outpace reductions in carbon intensity achieved each year.

Curious how AgriWebb is supporting corporations on this journey? Download our Sustainability Brochure to learn more.

Australia

Australia

New Zealand

New Zealand

South Africa

South Africa

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

United States

United States